Personal Mapmaking

Tactical planning for a 100-mile race (maps are metaphors — build your own)

Do you remember the fascination of exploring the maps that came with each month’s National Geographic, those special and specific depictions of a place that had the magical ability to take you there, to pull you into that place so you could look around? Was it similar to the pure joy you felt when you took Google Earth for a spin that very first time? Did it make you hungry for more?

I’ve always loved maps, and apparently I’m not alone, because I keep coming across novel new ones that pull me into their version of the world for long periods (I put links to some of them at the end of this section).

Maps as metaphors

One of the best descriptions of why we need maps (in all senses of that term) comes from an amazing old book called First Principles 1:

The piece of rock on which we stand can be mentally represented with something like completeness: we find ourselves able to think of its top, its sides, and its under surface at the same time; or so nearly at the same time that they seem all present in consciousness together; and so we can form what we call a conception of the rock. But to do the like with the Earth we find impossible. If even to imagine the antipodes as at that distant place in space which it actually occupies, is beyond our power; much more beyond our power must it be at the same time to imagine all other remote points on the Earth’s surface as in their actual places. Yet we habitually speak as though we had an idea of the Earth—as though we could think of it in the same way that we think of minor objects.

—Herbert Spencer, First Principles (1867)

Of course a map is not the territory, it’s a metaphor for the territory (or an idea, or a system or concept) — a specific symbolic representation of a territory that intentionally emphasizes some things and leaves others out, with each of those decisions aimed at helping us with a particular problem — usually a problem of visualizing something that we can’t directly see, and often can’t even comprehend without the symbolic representation that the map provides.

Let me orient you to the map…

That’s a standard first thing in military briefings: orient your audience to the map and give them context for the details that will follow. Here’s the big picture. Here’s a more focused picture. Here’s our specific picture, the enemy, the forward edge of the battle area, our location… Preferably this is presented on a physical map of the terrain that you can gather around, point to. You can’t really understand a plan until you can see and understand those things.

Personal Mapmaking

I’m in a version of that orientation process right now.

It’s a key part of my preparation for the hundred-mile trail race I’m running in a couple weeks (Pinhoti 100, in Alabama), an indispensable part of my tactical preparation for the race.

A hundred miles is too much for me to comprehend as a whole. To take it on, I have to simplify it, create a metaphorical representation of it that specifically leaves out many details, while drawing out other details that I might not otherwise see.

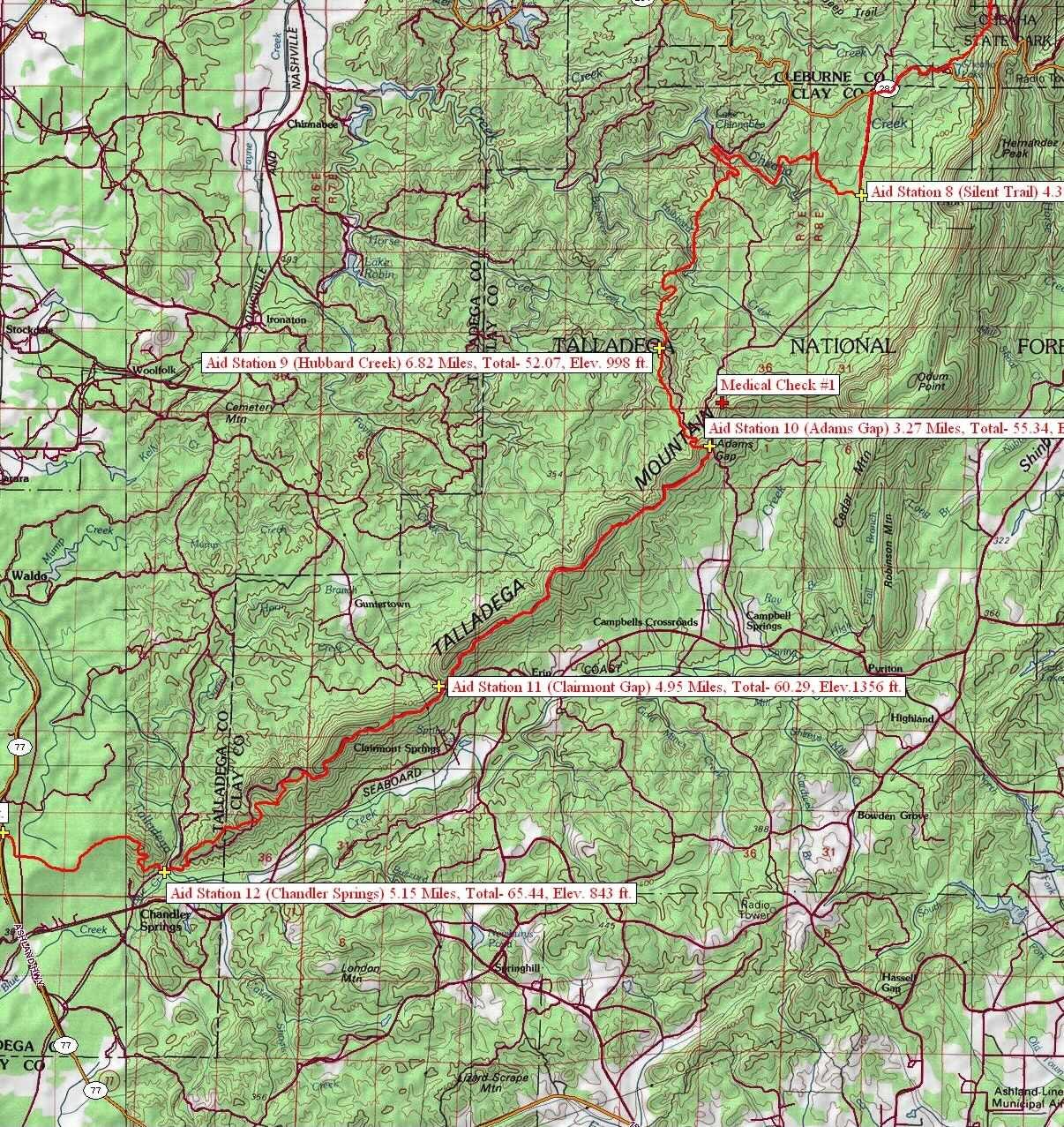

I start by orienting myself to the existing maps, usually a topographic map of the race route like this:

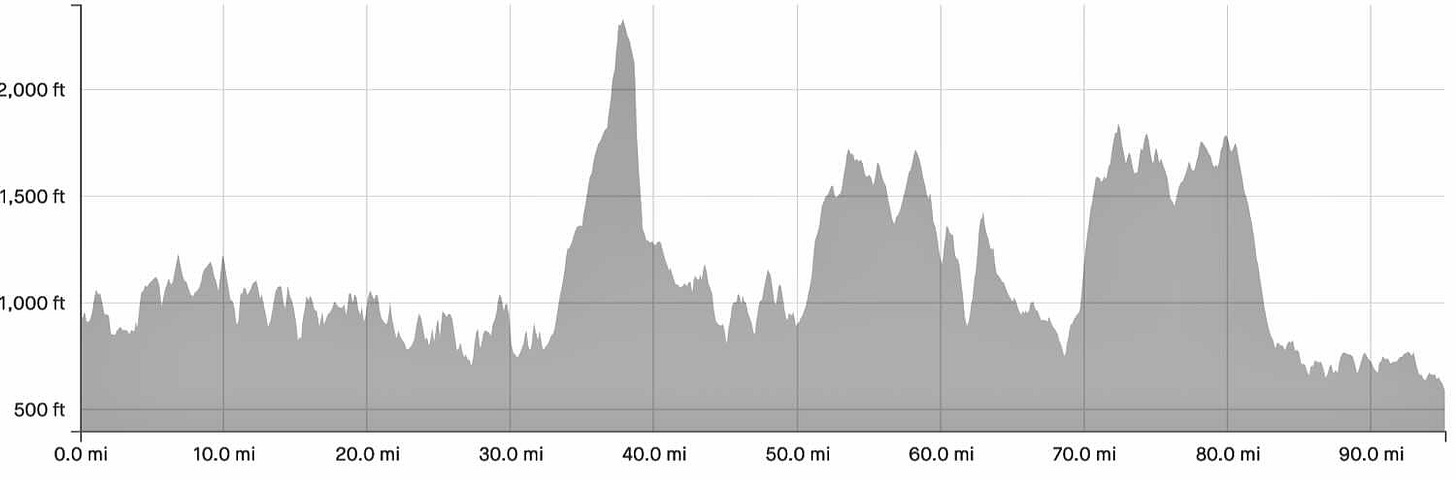

That’s helpful in getting me oriented and giving me context for the race, but I don’t care nearly as much about all those turns and squiggles as I do about the ups and downs, so next I go to a simpler map that shows only those ups and downs — the elevation profile of the course:

But that’s still more than I can really keep straight in my head. I need a different sort of map — a table that shows me distances between aid stations so I can visualize each segment of the race in sequence. I can then group those segments into sections, to plan my nutrition and hydration around, and I can associate those sections with a simplified version of the profile.

So… I get the big picture, then break it down and structure it in a way that makes sense to me. Instead of “a hundred-miler” I end up with maybe 15 or so small segments, grouped into four or five sections. I make it comprehensible, and therefore achievable, by simplifying it.

Of course this mapping concept works for much more than just racing, or even for movement through the physical world. My calendar is a map of my time, my file structure in Finder is a map of my digital documents, my task lists are a map to help me find my way through to the goals they support.

The bottom line for all of this is that maps are more than just interesting artifacts, they are metaphor-based tools that help me visualize and navigate not only physical terrain, but life in general.

Build yourself better maps, be a more effective human.

Some of my recent map (and map-related) finds:

Drop a raindrop anywhere in the lower 48 and see its path to the ocean (along with the name and length of each river along the way): River-Runner.

Draw all the roads (and only the roads): City Roads.

Draw the peaks: Peak Map (from the same source as “city roads”, above). Fascinating and fun — be sure you “Click here to draw peaks” and then click “Customize…” and then click “show options” (and then play around with those options).

Interactive Map of Pennsylvania County Formation History Press “Play” to watch the boundaries change through the years, or click a specific year to see how things were then. (Find a similar map for your own state here: Historical Atlases and Maps of U.S. and States).

Metaphor Map (a newsletter).

Cognitive Bias Codex — a fairly comprehensive “map” of our various irrationalities.

To Share:

Some share-worthy things I’ve found in the past couple weeks…

From The New Yorker: Behold, I Have Returned From a Hike. Honestly, we probably do overdo it sometimes, don’t we?

From Semi-Rad: I Recommend Wikipedia. He gives the best description of our relationship with social media that I’ve seen, that it’s like digging through a bowl of dirt to find a few M&Ms that might be mixed in with the dirt. As an alternative, I too recommend Wikipedia. Following your nose in Wikipedia is today’s version of the destinationless World Book wondering/wandering I mentioned in Rewilding (WtR #9), with a candy:dirt ratio that’s way better than Facebook’s. (And when they once a year ask you for a small donation, pay up — it’s hard for me to imagine a more worthy cause than “helping create a world in which everyone can freely share in the sum of all knowledge”.)

I followed the Wikiquote link from the Wikipedia main page and found this gem under “Quote of the Day”:

Great artists make the roads; good teachers and good companions can point them out. But there ain't no free rides, baby. No hitchhiking. And if you want to strike out in any new direction — you go alone. With a machete in your hand and the fear of God in your heart.

—Ursula K. Le Guin

Sorry, but I can’t resist a reading reference. I found First Principles in Jack London’s Martin Eden. I recognized myself in London’s description of his protagonist’s discovery of the book (and associated with it so much that I had to read the book myself):

…he got into bed and opened “First Principles.” Morning found him still reading. It was impossible for him to sleep. Nor did he write that day. He lay on the bed till his body grew tired, when he tried the hard floor, reading on his back, the book held in the air above him, or changing from side to side. He slept that night, and did his writing next morning, and then the book tempted him and he fell, reading all afternoon, oblivious to everything and oblivious to the fact that that was the afternoon…

—Jack London, Martin Eden

Wow, lots of things here to check out. Nice work, Jeff.