I came across the term “rewilding” this week, and it got stuck in my mind.

It’s not at all new — I’ve been continuously rewilding my private landscapes (and thinking of it as rewilding) since we bought our first home back in 1992. But it was used in a different context this time, and as I followed the thread backward from the place I found it (Clive Thompson’s “Rewilding Your Attention”) through a series of tweets and articles to a 1944 C. S. Lewis lecture (“The Inner Ring”), it became clear that this term and concept is appropriate for much more than just talking about the state of your yard.

Those articles focus on diversifying what you read online, defeating the “intellectual monocropping” the various social media platforms are designed to present. “You open your algorithmic feed and see rows and rows of neatly planted corn, and nothing else”, says Thompson. Add our innate Fear Of Missing Out and our gravitation towards that Inner Ring, and those algorithms become a powerful force that requires determination and conscious effort to defeat.

You defeat them by rewilding your attention. That means reading (and listening and viewing) more broadly, both online and off. It means seeking out the things the algorithm isn’t showing you, finding sites off the beaten path, being diverse in your newsletter subscriptions.

And it means following your whims, following your nose, wandering and wondering and wandering some more. It means allowing serendipity into your book selection process. It means being consciously receptive.

When I was a kid, my attention didn’t need rewilding — it was already quite wild and free. I’d settle in with our World Book encyclopedia (the old hard-copy, 20+ volume set), pull a volume at random, open to a random page, and start reading. From that first topic, I’d follow whatever trail I found, topic to topic, book to book (no hyperlinks needed), and three hours later I’d emerge, enriched and hungry for more.

My analog for this as a student at Penn State was to wander into those glorious Pattee Library “stacks” where the old books were stored. Choose a random floor (half-floor, really — two per story), pick a path through the maze of heavily loaded shelves to an empty desk, then choose a random title from a nearby shelf, and submerge. I still do this occasionally, and it only whets my appetite for more.

Rewilding is an intentional de-domestication. It assumes there are things that were better in their wild state than in their current tame state. It assumes that we are better in our wild state, or at least that we’re better if we’re in touch with that within us that is still wild.

And it applies to far more than just our reading lists and online habits. It’s an approach to life more broadly. Yes, of course rewild your attention, diversify your reading lists and your Netflix queue, but also…

Rewild your running (or your experiences in general). As I write this I have one conversation going with a friend about a potential through-run adventure, and a second conversation with another friend about how, sooner or later, we’re going to need to run a 200-miler. When is the last time you intentionally chose to do something new, something wild, or even better, something that frightened you?

Rewild your landscapes (both inside and outside). If your house looks like everyone’s house is supposed to look in the magazines, if your yard looks like your neighbor’s yard, it (and you) could probably use some undomesticating.

Rewild your diet. Literally, as in eating pastured meat and wild game and organic produce instead of industrial products. Figuratively as in trying different cuisines, different vegetables, different schedules. And maybe experiment with your various addictions (more on Sober October in an upcoming issue).

Rewild your friend group. If your circle is an echo chamber, you might as well be talking to yourself. Make sure that not all of your friends are runners (or liberals, or hunters, or skinny people, or any other all). Have friends who are both older and younger. And have a look at Venkatesh Rao’s “Don’t Surround Yourself with Smarter People” where he explains his realization that what he really wants is people who surprise him: “The trick is to surround yourself with people who are free in ways you’re not. In other words, don’t surround yourself with smarter people. Surround yourself with differently free people.” (There’s a lot more to it than that — read the article!)

By all means, hold on to the domestication that helps you, that pleases you — it’s not all bad. My goal for myself is only to be deliberate, to question each part of it and make sure it does serve and please me, without assuming that it must be so.

Reading (responses)

The last issue (Reading: everything, all the time) drew more responses than any previous issue. No wonder: reading is special to many people in a deep way. Among those responses…

Keeping track

It prompted one reader to check their “books I’ve read” list — the Excel (or Google) sheet that those of us who keep such things have for keeping track. He has 689 books on the list, but has only been keeping track for about 15 years. My own list goes back twice that far, to about 1990, and has 856 titles (I so much wish I’d started it much sooner). Of course it’s not a competition, and it’s so much more about quality and variety than quantity, but it’s still nice to know.

The limitation of words

Larry Creveling sent an insightful post he wrote recently about the inadequacy of words — how the truths we perceive are beyond our capacity to express with words. I think that limitation, that gulf between what we experience and what we’re able to convey, is a reason we (humanity) keep trying over and over again to say the same things in slightly different ways — we never get it right because the words aren't there for it, but we see glimpses of it and feel like we have a responsibility to keep trying. His closing sentence sums it up perfectly: “Humbly, then, I continue to attempt to put into words the magnificent discoveries I wish to share.”

Words into action

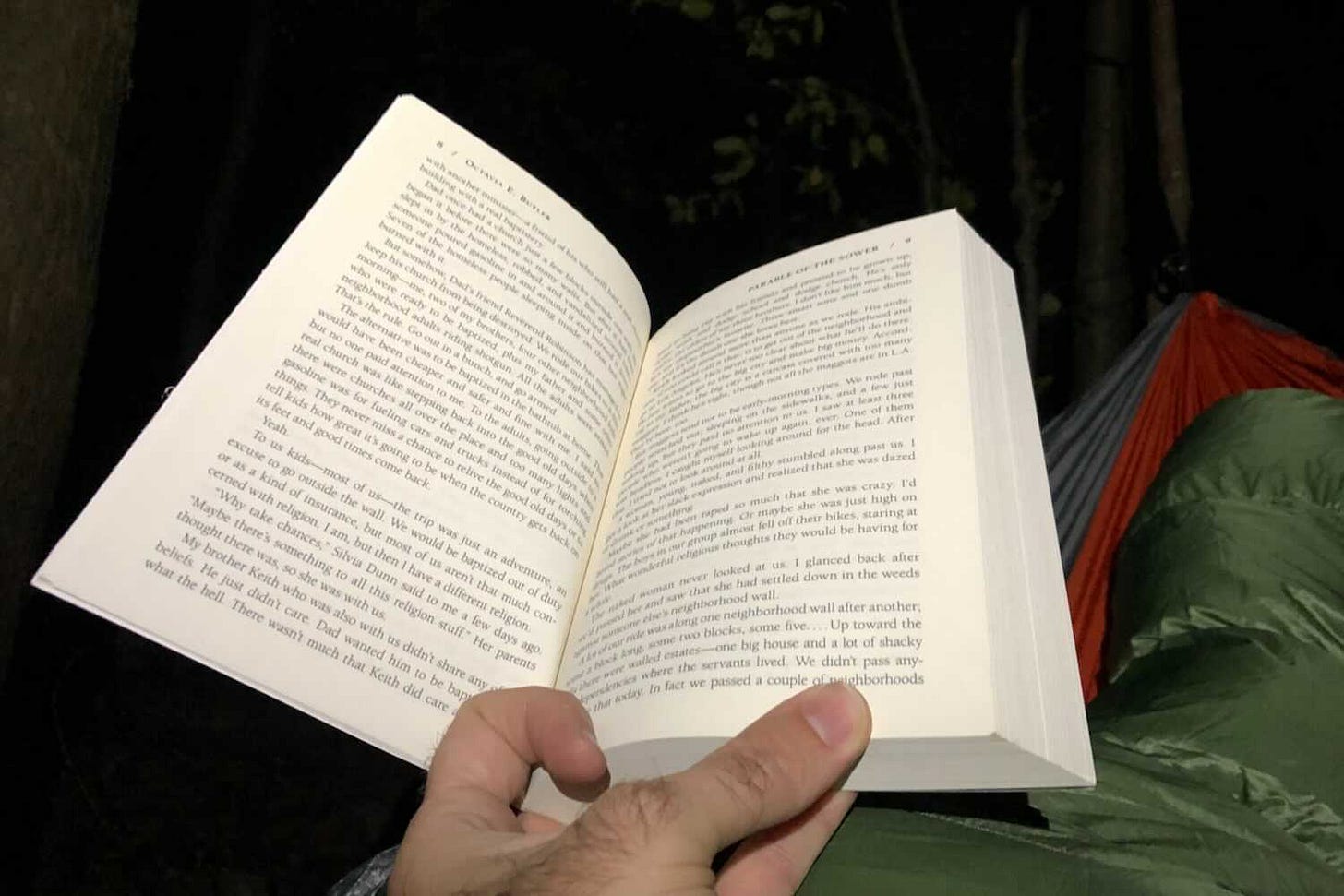

This photo was sent to me from an overnight outing on the trail — a hammock, a headlamp, and a thick-and-open hardcopy book. Does it get any better?

Functional Illiteracy

And my last reading reference for this issue (please tell me you’re not among the “functionally illiterate” therefore incompetent):

We have been fighting on this planet for ten thousand years; it would be idiotic and unethical to not take advantage of such accumulated experiences. If you haven’t read hundreds of books, you are functionally illiterate, and you will be incompetent, because your personal experiences alone aren’t broad enough to sustain you.

— General Jim Mattis, from “Call Sign Chaos: Learning to Lead”