It’s (finally) Hardrock!

So, I’m running Hardrock next month.

Getting there has been a long (and wonderful) journey. When I learned about the race in 2014, I was new to trailrunning, and my longest finish was a 50k. I ran my first hundred the next year, my first qualifier in 2016, and I entered every Hardrock lottery from then until they drew my name for this year’s race.

Meanwhile, I ran lots of miles, a bunch of ultras, and had some adventures.

Each of them was an end in itself, but also, they were all leading me to, and preparing me for, this one — the most challenging race of my life. It’s a culminating test of everything I’ve learned, the last of my lifetime A-races1 (and the first race of my 7th decade).

As such, Hardrock already demands my very best effort. But I feel an added sense of responsibility because there are hundreds of runners (each of them at least as qualified and dedicated as I am) who weren’t as lucky as I was on lottery day. And thousands of others will be watching and dreaming and perhaps seeking inspiration from the race. That’s why a spot in this race, more than most, brings a special obligation to use it well.

“I can only make sense of my unaccountable good fortune by assuming that it means I am under special obligation to make good use of it.”

— Marilynne Robinson (novelist)

My Training Plan

For me as a writer, part of “make good use of it” is to bring you all along for the ride. So months ago I started writing this post, to share my training plan...

…and I promptly got stuck.

In my well-intentioned hubris, I thought I could write some grand Training Manifesto worthy of the magnitude of the coming challenge and the prominence of the Hardrock stage.

Turns out, I’m not qualified or equipped to produce such a document.

What I can do is share this outline of my training plan, with some of the thoughts behind it, and some of my parameters for using it. It’s no grand manifesto, only my personal best guess at what will work for me, based on my particular (and ongoing) experiment-of-one.

This is the evolved descendent (the 56th iteration) of the plan I used for my first marathon (in 1998). I’ve used it for every marathon and ultra since then, tweaking it each time, adapting it to the current circumstances of my life, experimenting, optimizing it for my personality and my changing (aging) body, doing my best to get it right.

Again, it’s specific to me, but maybe you’ll find something in my process that helps you with your own process.

General Framework

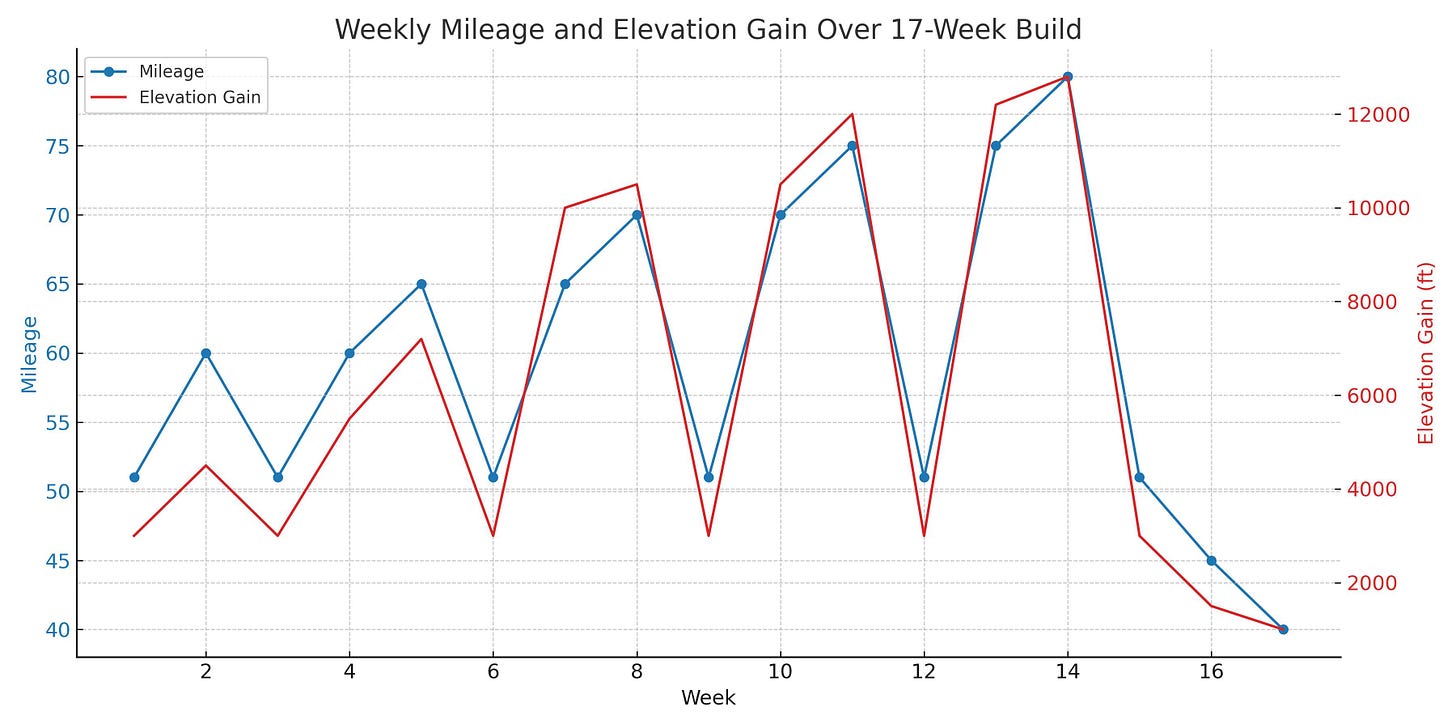

Training plans are personal, and there’s a wide range of opinions about volume and frequency and content and style. But if there were an “industry standard”, my plan is probably close to it: an 18-week framework that, through a series of building weeks and recovery weeks, gradually reaches a peak at about Week 14, then tapers to the race.

Within that framework, there’s room for significant variation — in the arrangement of those builds and step-backs, the timing of the peak, the length of the taper, and in the structure and content of training within each week.

Weekly Pattern

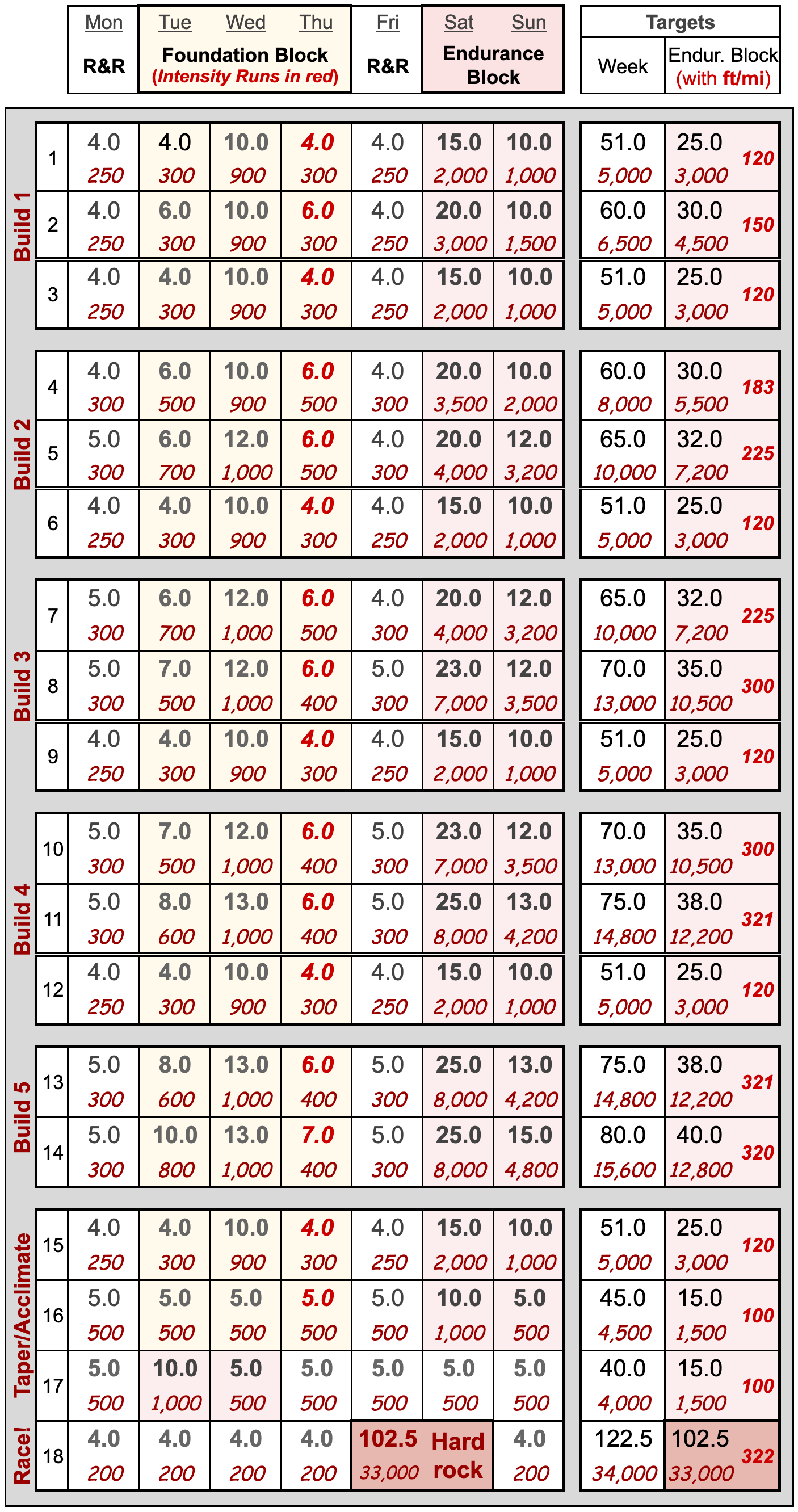

My week goes like this: a rest day, a midweek Foundation Block, another rest day, and a weekend Endurance Block. That’s it, over and over for 17 weeks, until race week.

Endurance Blocks feature back-to-back Saturday/Sunday long runs with lots of ascent, the primary stimulus for building long, steady climbing strength and fatigue resistance. They are the most important part of the train-up, and I work (and adjust) everything else around them.

Foundation Blocks include three runs — a short one, a medium one, and an “intense” one. The first two are for endurance, to build mileage and give me consistent time-on-feet and develop aerobic capacity. The intensity session is for speed, and while this is a secondary concern for a race like Hardrock, it’s not unimportant (shaving even a few seconds per mile from my sustainable baseline cruising pace adds up to significant time over 100 miles, and speed work is a way of doing that). These intensities will be mainly fartleks, unstructured speed play (the Calvinball of running — joyful, make-it-up-as-you-go chaos, pure gold when most of your runs are long and slow).

R&R days are for all the R’s: rest, relax, recover, regroup, reload, reconnect with underlying purposes… They are not days off, but the runs are short (4 or 5 miles) and super-easy, with absolutely no pushing, no pace targets, no counting steps, no pressure. I call them Rambles, and they are as important to the effort as the big weekend runs.

The Builds

I’m using a step-back model for this train-up (it’s actually a “two steps forward, one step back” model). I’ve divided those 18 weeks into five 3-week “builds”, each with 2 weeks of building and 1 week of recovery. Each build starts where the previous one left off, then pushes up both volume and difficulty in the second week. The recovery week steps back to base level, and then the cycle starts again, ratcheting up from build to build. In the final build, the step-back week is also a transition into the taper (which in this case will also be the start of travel and altitude acclimation).

I’ve played with many variations of this through the years, and drifted towards a single, steady build to a single peak, without recovery weeks. I don’t think there’s a good physiological reason for step-backs (I think the important physical recovery happens within the cycle of the week). But, I think the psychology of step-back weeks might be a different story, and I’m counting on that to help me focus through the whole thing (so far, it seems to be working).

So, structure the week, group the weeks into builds, set targets, prescribe daily doses to meet those targets… when it’s done, it looks like this (miles above, feet in italics below):

Some Considerations

Volume

My weekly volume climbs from around 50 miles at the start to a peak of about 80 miles. I know from experience that if things go well, I can handle that and benefit from it (grow from it rather than be damaged by it). A difference this time: I want to sustain that high (for me) volume for more of the train-up (if I hit my chart totals, I’ll have my biggest train-up ever, with about 1,000 miles and 145,000 feet of climbing in the 17 weeks before the race2).

Some runners will double that total; others will succeed on far less. I’m pushing things on this front because I believe that, all else being equal, the more miles you run and feet you climb during the train-up, the better your race will be.

But… all else is rarely equal, and the key to a good train-up is how you make your compromises around that principle:

how much volume can you give yourself without breaking either your body, your spirit, or the functionality of your life beyond running?

how well can you mitigate lower volume by improving the quality of the volume you keep?

Specificity (altitude and ascent)

Training for Hardrock is all about elevation, in terms of both altitude and ascent. Success or failure depends on how well I prepare for each of them.

Ascent. Hardrock has about 33,000 feet of ascent (a climb density of about 323 feet per mile). It gets most of that gain from eight big climbs (in rough terms, four are between 2,000 and 3,000 feet, one is ~3,600 feet, two are ~4,400 feet, and one is ~5,400 feet).

Our Allegheny Mountain trails here in Pennsylvania can be just as steep, and on average they’re more technical than the Hardrock trails, but the biggest climb in my area is only 1,400 feet. So we do repeats — lots and lots of repeats.

To get more specific with that, I chose the climb density of my weekend Endurance Blocks as my key metric. I start in Week 1 with a weekend target of 25 miles at 120 ft/mi, reach 35 miles at 300 ft/mi by Week 8, and peak with 40 miles at 320 ft/mi in Week 14. My experience at races with similar climb density (Manitou’s Revenge, UTMB) makes me confident this will set me up for success on this front.

Altitude. Hardrock goes over 12,000 feet above sea level at least eight times (including once over 14,000 feet) and rarely dips below 10,000 feet. I live and train at about 2,000 feet.

No amount of climb training at this altitude can mitigate the effect of racing at that altitude. So, for this one (once-in-a-lifetime) race, I’m going early, moving to altitude for 23 days before the race. That’s probably not long enough for full acclimation, but it should at least get me through the initial physiological adaptations and into some of the secondary ones. And I’ll jumpstart the process at home with some intensive heat training before I head west.

Altitude really is the biggest wildcard of the race for me, and I think this will be enough to keep me in the game — we’ll see…

Discipline, formality, and flexibility

I’ve done strict and formal train-ups where I planned each run down to the tenth of a mile (with a “plan your runs, then run your plan” mantra), and loose versions with just some general parameters (like: I need to get at least 2 weeks with over 10,000 feet of climbing, and at least 3 weeks over 60 miles, and I’ll just make sure I get those in).

I’ve had successes and disappointments with each approach, but I’m pretty sure my sweet spot is somewhere in between: a full plan with specific targets and constraints, but with built-in points of flex where I can make subjective adjustments according to my performance and how I feel.

Which brings me to this: the best plan is only as good as the judgment of the person using it. My judgment works best when I give myself some guidelines ahead of time, so…

My Rules for using the plan

Flex Points (the cut list)

This plan is aggressive, a best-case scenario. The volume I’ve scheduled is at the outer edge of my capacity, achievable in full only if everything goes well. I’ve had quite successful races on far less training. This is not a plan to get me to the finish — I can already do that. This is a plan to set me up for the very best race I’m capable of.

As such, I fully expect that everything will not go well. There will be glitches, disruptions. Some niggling injury will threaten. Life will happen.

So I build flex into the system, and I have an ordered cut list of what I’ll shift or cut if I have to make adjustments:

Flex 1: Shift mileage and ascent within blocks. I show a daily prescription on my chart, but what I really have is a target for the block, and I’m free to shift within it. This lets me work around appointments, chase good (or bad) weather, good (or bad) moods, etc.

Flex 2: Cool down the intensity sessions. Speed work is low priority — great if I can get it, but if there are problems, I can downgrade the Thursday distance and/or intensity, or even make it an additional recovery run.

Flex 3: Cut midweek volume. This is my biggest flex point — the Foundation Block runs are medium priority, helpful but not critical. I can cut mileage and/or ascent from them as needed (just be sure it’s for something more legitimate than laziness — that’s a slippery slope).

Flex 4: Cut weekend volume. The Endurance Blocks are my priority training, the last thing to cut. But discretion over valor… if I’ve made the other cuts and still need more, I can cut mileage and/or ascent from the weekend.

Flex 5: Beyond that, a new plan. Beyond that, we’re in crisis mode — discard the old plan and work with the new situation. And remind myself that I’ve been there before. (Example: a knee issue subverted my training for Pinhoti 100 in 2021, reduced me to only walking for most of the last weeks. I almost didn’t start the race, then I ran my 100-mile PR.)

Non-negotiables

Those negotiable items — and having the self-awareness and discipline to use them well — are critical. But it’s just as important to know clearly what is not negotiable:

A daily warm-up/stretch session. I’ve honed this into a brief but comprehensive yoga-ish routine that I can get through in 10 minutes. If I don’t have time for the warm-up, I don’t have time for the run.

Long, slow starts. With each passing year, my motor takes longer and longer to get cranking smoothly. If I ease slowly and carefully into the first 2 or 3 miles, I’ll likely have a good run. If I don’t (because of over-enthusiasm, peer pressure, time pressure from another commitment, etc.), I won’t. If I don’t have time to start the run slowly… I don’t have time for the run.

No alarm clock. Sleep is a powerful training and recovery tool, and a shield against sickness and malaise. With rare exceptions, I sleep until I’m done sleeping every morning (a hard-earned privilege of retirement, and I have no qualms using it).

No cramming, no “catching up”, no schedule perfectionism. I have those built-in flex points and I will use them. But when I do — if I downgrade a run for cause (or a block or even an entire build cycle) — the original targets are gone. When my situation stabilizes, I pick up where I left off, or I slide the whole schedule back to the point of failure. High-volume targets are there to support the training, not the other way around.

Keep the streaks (an exception to “no perfectionism”). I run every day (since September 2017), and I do at least one 10-mile run every week (since July 2006). I’m not willing to yield on either of these right now — the psychology of this is far more powerful than the potential harm of running when I otherwise shouldn’t.

Augmenting the Plan

Other Training Intentions

Get my feet wet early and often. Feet adapt to repeated exposure and become resilient, but only if you ask them to. I get them wet during training (and leave my wet shoes on for a while after the run) so I don’t need to pamper them during the race.

Maintain metabolic flexibility. I did a hardcore keto reset in February to enhance my fat adaptation, I eat a relatively low-carb diet, and I do regular fasted runs to maintain that capability and build confidence in it. But I also fuel some runs, and force myself to consume at the level I’ll use for the race (roughly 20g/100 calories per hour).

Vary the surfaces. Trails are the best, right? But Hardrock has plenty of road miles, and I know (from painful experience) that if I don’t practice regularly on roads (and keep my lower leg muscles and tendons accustomed to them), roads will hurt me. So, many of my runs are hybrids, with some mix of both road and trail.

Get adversity runs. It doesn’t take many (one per month is probably enough) but I believe it’s important to have “bad” training runs, to learn to deal with various specific challenges, to become “comfortable with discomfort” and experienced at field expedient problem-solving. The race is not the place to bonk or run out of water for the first time, or get soaking wet and cold (or hot) for the first time, etc… If adversity doesn’t appear on its own, I seek it out or simulate it.

Pay attention. In an undertaking like this, it’s easy to slip into complacent routine. But I can consciously nurture my sense of wonder and a feeling of gratitude — I can embrace the rush of it all. Not only does that help my running, it aids my progress as a competent human, and keeps my focus on the journey rather than the destination.

Supporting Efforts

I’m clearing the decks to concentrate on this train-up and race. Over the past 4 months, I’ve made a concerted effort to physically and administratively “get my house in order” (a main reason I haven’t published here since December). I’ve been systematically working my way through a long list of backlogged tasks, closing things out (or deleting them), cleaning and clearing and simplifying. All of that to earn an ultimate athletic luxury: that for at least this brief period, I can fit life in around my running, rather than the other way around.

I’m doing morning treadmill climbs. These are strictly NRA (No Running Allowed), and the mileage isn’t on my plan. They’re just a way of gently raising my base level of daily activity, with minimal impact on my scheduled runs. I do 30 minutes on a 10-15% incline, at a pace between 15 and 17 minutes per mile, and while I’m walking, I listen to podcasts, or sometimes I focus on cadence with one of my pace playlists. And when it’s time for heat training, I’ll do these IOD (Intentionally Overdressed), then go straight from the treadmill to the sauna.

I’m cross-training at the climbing gym. On my rest days, I’ve been learning the basics of bouldering, hitting the wall for an hour before my leisurely rest-day runs. I doubt it has much effect on my running fitness, but I love the novel stimulus of it (both mental and physical). And I notice that when I go straight from the wall to the trail I feel more tuned in, my steps are more deliberate and precise (this has to be a good thing).

And that’s it, the meat of my training plan (and because it took me so long to get around to writing this, I’m already into the 1st week of Build 5, with only four big runs still ahead… all systems are still “Go”).

Next up, how about a plan for the race itself?

(I’m working on that — please stay tuned!)

Extras

Some things I referenced (etc.):

Towards public accountability for my effort… here’s my Strava link (where you can see if I’m actually doing what I’ve said I’ll do).

Those pace-based playlists I mentioned? You can find them on my Spotify profile.

My Pinhoti race report (mentioned above): Pinhoti 2021. A note about this one… I hadn’t looked at it for a long time (it’s on my old website), and I’d forgotten much about the race. I also forgot how very detailed this report is — far more than I usually write. If you’re interested in details, I feel like I did a good job of presenting them in this one. Also, my Substack post “Bewildered (gratitude and greed)” linked below (and much shorter), looks at that Pinhoti race from a different perspective.

Related posts from me:

Related items from fellow runner-writers:

an excellent synopsis of Hardrock’s history and allure: Wild & Tough (Telluride Magazine) from

. Sarah is running Hardrock this year, too, and writing eloquently about it inrecent timely advice on flexibility in training, from

: Protect Tomorrow's Run and : Beware the rigid training schedule

Attribution:

I lifted the Marilynne Robinson quote straight from James Clear’s newsletter (on the day I started this post): https://jamesclear.com/3-2-1/april-10-2025

My personal “Big Four” hundred-mile races:

Eastern States. Yes, of course your hometown race should be on your lifetime A list. (completed in 2015)

UTMB. The closest I’ll ever get to an Olympic experience, and the hardest race I’ve run… so far. (completed in 2017)

Western States. Trail-running’s Boston Marathon (completed in 2023)

Hardrock. (coming soon!)

For context, I did 815 mi/94,000 ft in the same time frame last year for Bighorn, and 975 mi/112,000 ft for Western States in 2023.

Love this plan, especially the built-in (and documented!) flexibility. Seems like you should be at altitude or heading there soon, yes? Best of luck... Can't wait to read more.

Wow Jeff, your details always intrigue me. Sounds like a recipe for success. The fun part is always the “execution” of it all😉

It’s been nice following along on Strava and watching your training plan unfold. Now go out there and Ace the test! Will there be tracking? If so, let us know.

Happy Trails!