I’ve tried to start on some other topics, but it’s futile — there’s one thing dominating my waking thoughts (and some of my dreams) right now: the Eastern States 100. So I’m going to stop fighting it and just tell you about this race that is fast approaching.

Some of you are intimately and extensively familiar with this 100-mile footrace we hold each August, but most of you probably aren’t, so let’s start with an overview of the race, and a bit about the behind-the-scenes work that goes on before and during the race (which might help you understand why it monopolizes my attention — I’m the logistics coordinator, and president of the non-profit board that oversees it).

Eastern States overview

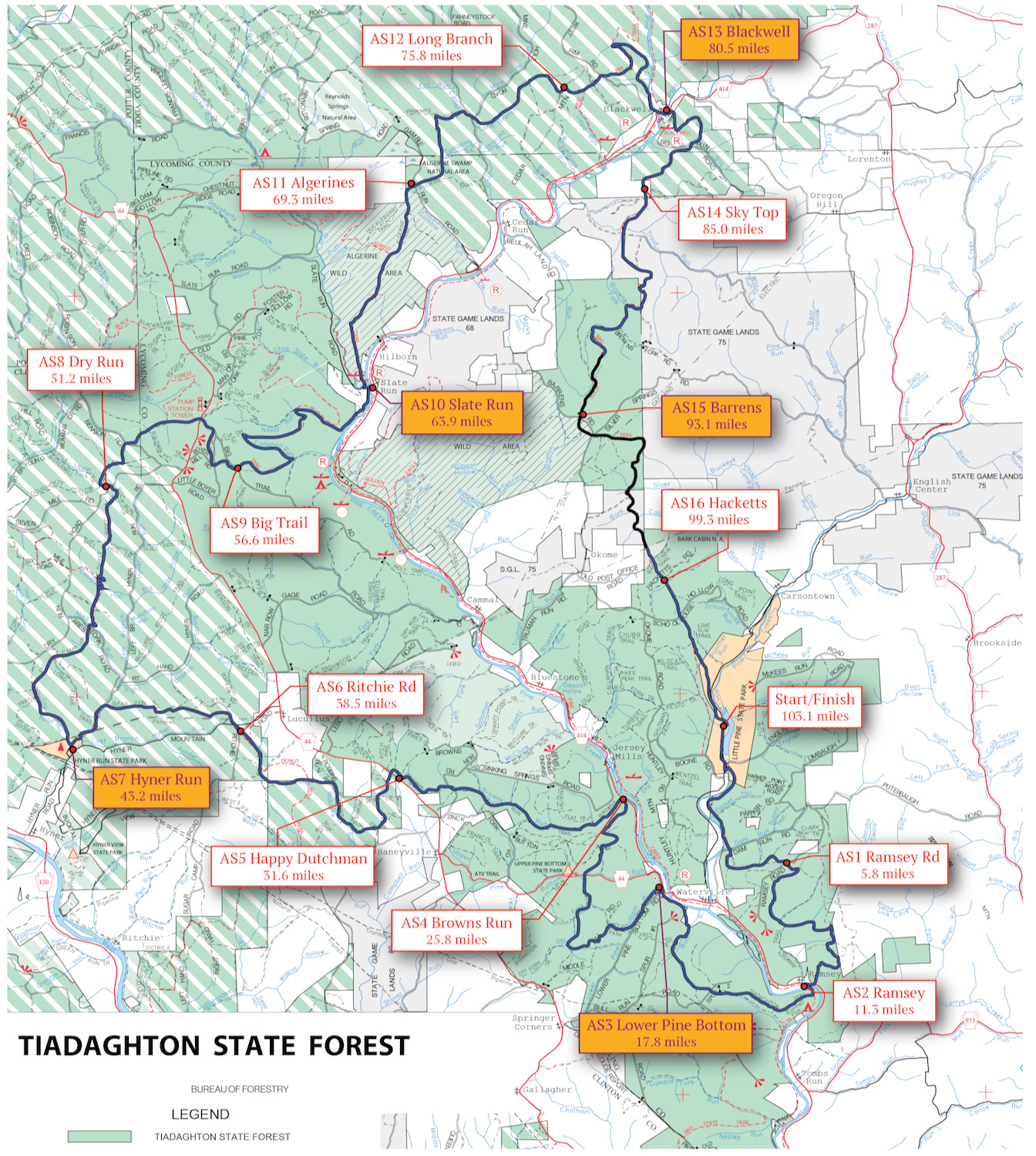

On the weekend of August 14th, about 190 men and 40 women (aged 21 to 62 — but there’s no age limit), will travel from 25 US states and 5 foreign countries to race headquarters at Little Pine State Park, near Waterville, PA. At 5am Saturday morning, they’ll run south from the park on the Mid State Trail, beginning a 103.1-mile clockwise loop that will take them through three counties, two State Parks, three State Forest districts (including two Natural Areas and two Wild Areas), and two sections of State Game Lands, on at least 24 named trails. They’ll climb over 20,000 feet (and descend just as much) during this circumnavigation of Pine Creek Gorge.

Wolf Path (below) is an example of a typical Eastern States trail — steep and rocky single-track that follows a small stream (a “run”) up past its source, crosses the mountaintop, then drops into the next watershed. Over 95 miles of the route is on single- or double-track trail.

We have to clear and mark all those trails. Pennsylvania winters (and the summer storm season) are rough on them. It takes hundreds of hours of hard labor to clear the blow-downs and debris (and prune back the laurel and rhododendron and nettles) to get the trails race-ready.

We set up 16 aid stations to support runners and track their progress around the course. We stock them with water, food, ice, medical (and emotional) support, and our enthusiastic volunteers help runners with whatever they need to get them on their way to the next station.

The race winners are likely to finish in less than 20 hours (the course record is 18:23:47), but most runners will still be out at second sunrise on Sunday morning, and some will use the full 36 hours before the finish line closes at 5pm Sunday afternoon. This variation in pace means the field spreads out as the race progresses, and the pass time (the time from the arrival of the first runner to the departure of the last runner) gets longer at each aid station. At most, it will take 3 hours for all runners to pass through aid station 2 at mile 11, but it could take as long as 18 hours to get everyone through aid station 16 at mile 99.

A synchronization matrix (below) helps us visualize the support challenge as the race progresses. The horizontal axis shows distance (as aid station mileage across the top), the vertical axis shows time, and the blocks in red show the expanding footprint of the runners in time and space as they move through the course. (Gray shows hours of darkness.)

For example, at noon there are only four stations open (AS4 to AS7), and runners are spread over about 17 miles at most. But by 10pm, there are nine stations open (AS8 to AS16) and runners could be spread over as much as 48 miles.

This is a remote area, with very little cell service, and the drive time to the farthest aid stations can be as much as an hour one-way, so runner tracking and emergency planning are crucial. To handle the task, we rely on volunteers associated with the PA Emergency Management Agency, local first responders, and a dedicated network of HAM radio operators who work at each of the aid stations, giving us reliable communications and emergency response capabilities. And we have medical volunteers out on the course.

All told, we’ll have a small army of over 200 volunteers involved in making this race go, keeping it safe and successful. And they keep coming back year after year, despite — or maybe because of — the long hours and hard work. It truly couldn’t happen without them.

Why?

The simple bottom line is that this is a hard race to run, and it takes an immense amount of work to put the event on. So the obvious follow-on question is… why do it?

There are at least as many answers to that as there are people involved, and we each have multiple answers. But I always come back to a single indelible memory (maybe it was a revelation) from the inaugural running of Eastern States back in 2014.

I’d paced a friend from Slate Run to Blackwell, and I was waiting at the Blackwell aid station for another friend who was running without a pacer or crew, thinking he might want company for the final push to the finish.

It was maybe 2am or 3am when the storm hit, a long and torrential downpour. I don’t know how many runners came through during the storm, but there were many, and of course the conditions were the same for each of them — they’d each covered 80 miles of difficult terrain to get here, they were each drenched and cold and tired, they each had more than 20 miles and three big climbs between here and the finish line.

But there were some striking differences in their reactions to it all.

Some of them were clearly broken. The light in their eyes was faded, there was a look of defeat on their faces, and it was clear that they were not going to continue.

Others were suffering, but the light was not gone. They stopped, sat down, had soup and coffee, tried to delay their departure, maybe hoping the rain would stop. But they eventually got it together, and with grim and determined looks, they got up and limped forward into the rain.

But there were a couple runners who were different — who seemed invigorated by the ordeal. I’m picturing one guy in particular who came in shivering but smiling, grabbed a few things from the food table, gratefully accepted a black garbage bag in lieu of a rain jacket he didn’t have, and then headed back out into the storm. He was smiling when he arrived, he was pleasant but focused at the station, and he was smiling when he left. His enthusiasm was intact and it seemed like the miles and the rain had made him stronger and better.

The crux of the whole thing is there in that moment, the torrential rain at 3am moment. How do you react, how do you handle yourself, what kind of runner — what kind of human — are you? As I watched, I knew I needed to answer that for myself. I thought I already knew the answer, but I also knew that there’s only ever one way to find out for sure…

So if you ask me why we do hundred-mile races, that’s it right there — to find out if we can smile through the darkest moments and be stronger and better in those moments.

And if you ask me why I’d spend so much time and energy working to make an event like this happen, I’d say it’s all aimed at creating a moment like that for someone else, to set a stage where they can find out for themselves who they really are.

For some people that moment will come during a 3-in-the-morning thunderstorm. For others it will be at 3 in the afternoon when it’s 93F and they’re on an exposed stretch of trail under the blazing sun. Or it will come in this, or this, or this other tough situation. The point is that hundred-milers, and especially the hard ones like Eastern States, provide a very large stage that can reliably present these potential moments, these opportunities.

Anyway, that’s not the only reason I’m involved, but it’s a fundamental one. And I think it’s important, worthy of my time.

Until next time,

Jeff